My first CESO Assignment – A Recollection of Guyana

I step off the Air Services plane (population 5; plus pilot) in Lethem. There to greet me is my contact for the assignment.

“Welcome”, he says.

“Thank-you”, say I.

“Welcome”, he says again.

“Thank-you”.

Repeat once more. Finally, I realize there’s another word before, “Welcome”, which turns out to be “Roldan”. So…not an arrival greeting then. He is telling me his name! Roldan Welcome.

I am the CESO Volunteer Advisor to the Rupununi Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Lethem, the largest town in the high savannah of Guyana. My assignment will take me through indigenous communities from Surama in the north – a well-established resort – to the administrative village of Aishalton in the south where, exactly a month before, they had their first telephone service. Ever!

The savannah spaces are gorgeous, bounded on most of one side by the Kanuku Mountains. Cattle ranching country and, in fact, the largest unfenced ranch in the world is here, Dadanawa. The sort of space where God would choose to place his country club, assuming he wanted one! And the wondrous air – in the past 48 hours I have experienced the longest closing of Toronto airport due to an ice storm, followed immediately by the stifling heat-blanket of Georgetown. This…is heaven.

The first community I will visit is Moco-Moco. How I am to get there is uncertain, as indeed is every travel arrangement in the Rupununi. Roldan Welcome’s sole, and only, mode of transport is a bicycle with only one pedal. Now, those are hard to ride! Roldan has also given me the secret to success in the Rupununi. It’s one word: “flexible”.

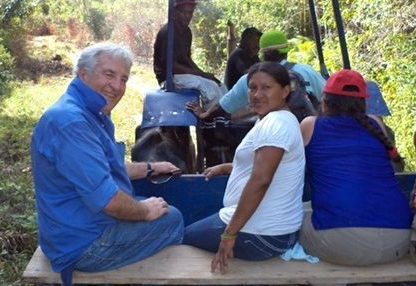

In the morning, it’s off to the Benab in St Ignatius. There I learn that the conveyance to Moco-Moco consists of the community’s tractor, with trailer, which will take us well over an hour along the two-lane ruts at speeds well in excess of 2 mph!

I eventually realize that the conversation between the toshao (chief) and the others involves a discussion as to whether this elderly (and likely a bit decrepit?) Westerner will be able to climb into the high trailer. Up I hop. And we’re off; sort of. Our progress is so slow that in the afternoon, we will be overtaken by two young girls on bicycles pedaling over the grassy hummocks alongside to pass us. Grinning.

Kidneys shaken and jumbled, we arrive at the village of adobe walls, with thatched roofs, perhaps two dozen houses dotted picturesquely into the landscape.

Under the cooking shelter, I watch the women, spellbound, as they prepare food. The tasty cassava bread which they make by squeezing the pulp out of manioc through a matapee as it can be poisonous uncooked. The bread is then dried in the sunshine on banana fronds. I watch them prepare their traditional dish of pepper pot. It consists of the rather vague term “bush meat”, some species of which are deduced from the bleached skulls which decorate the rafters. What all of them are, I have no idea, but there does seem to be a good representation of armadillo! And casiri, a dish made from potato.

Well-provisioned, we set off for the Matapee Creek Falls on an outing which involves the entire village and seems to require a cacophony of young girls giggling. Walking single file, a young girl ahead of me, using only one hand in a single motion, grabs a stick from the ground, swings it overhead, drops the stick and catches the falling…what is it? The movement is ballet-like. She shows me a round, red-pepper-shaped fruit. The first cashew fruit I have ever seen. She bites into the fruit and offers me a ‘slurp’ – it’s tart and sweet and utterly delicious. To hell with the cashew nuts themselves, if you can have a taste like that!

At the base of the falls, we have reached our destination. Frothing water and intense dark pools shaded by impenetrable forest growth. Some of the men notch

their small bows with long arrows and aim into the water. Their aim is uncanny – each shot seems to bring another fish to be added to the grate over the fire. The children all splash about in the pools as lunch is prepared – fish, pepper pot, cassava.

Alton Primus, tourism director of the village, wants to show me the ponds upstream. We scramble over rocks and through very dense undergrowth and he identifies much of what I keep finding myself entangled in. Especially the “waita-minute”, whose spines snag your clothing as you pass by, and after a few steps, its pliancy boomerangs you back to where you started!

Alton, who is an utter treasure of a person, shows me a hidden pool, and we swim. These areas cannot seem very different from the Rupununi savannah that Evelyn Waugh traversed on horseback (probably faster than us!) nearly a century ago. The water flowing into this rock pool is blessedly cool and completely transparent – wonderful. Alton tells me he will call this “Roger’s Pond”. I am flattered but wonder whether he has christened this pool before? At the same time, I realize that perhaps fewer than a half dozen Westerners – and perhaps none at all – have ever seen this particular hidden pool.

On the way back to the village group, I slip and cut my finger. The wonders of village medicine! A woman cuts a twig of a shrub, “bloodwood” she calls it, and dabs on the latex-like sap which seals the wound instantly.

On returning along trails to the village, we have a meal and chat. We continue conversations about the medicinal plants – one of the young women mentions “Granny’s Backbone” and I ask what it’s used for? After some giggling and a little blushing, she offers that it’s “something for men”. Aah.

And so, to work…

I am in the Rupununi to investigate possibilities for sustainable tourism in the indigenous communities. I mention “cultural tourism” and after a long silence one of the older women offers, “But we don’t have any cultural tourism”. I am stunned, and recount what I have discovered today!

I’d never seen a cashew fruit nor tasted its juice. I’d never tasted sun-warmed cassava bread, nor seen a ‘matapee’ used; let alone the ancient knowledge of its use. I’d never seen bow-and-arrow caught fish. By fishermen who did not miss once. I’d never been introduced to the skulls of all the animals that may go into a pepper pot. I’d never had a bleeding wound sealed with tree sap. Never been shown the

“Bird Party Tree”. Never had a pond named after me. And on…and on.

And, finally, I admitted that while the setting of the outdoor meal we were enjoying was reminiscent of growing up with ranch life in Kamloops, BC, rather few of those long ago ranch meals featured entertainment by a blue-and-red macaw sitting in the bush over my shoulder making it impossible to hear. Or the flocks of parakeets flying overhead.

I assured them that if they made any future visitors as welcome as they made me, and shared so much of their life ad they had with me; that was the very essence of sustainable, community-based tourism!

My grandmother always said, “Nothing precious lasts forever”, and that day couldn’t. As I left, I asked a group of young adults if there was anything I could help them with. A young man said he could be helped showing visitors birds in the dense tree canopy if he had a green laser pointer (red startles the birds). And I can attest to how difficult it is to spot the birds that he sees so naturally. And a young woman asked for a cookbook for her mother. “Not every Westerner likes our food, and my mother doesn’t know how to cook any other”. “It could be a used book”, she added.

So, dear readers…I have their addresses, and if any CESO volunteers are on their way to Lethem…

Donate Today

Your donation helps connect businesses, governments and community organizations with the skills and support to achieve their goals and contribute to inclusive growth. When you give to Catalyste+, you empower women and drive progress in harmony with nature. You’re helping people get what they need to improve their lives and build strong communities.